In this post, I would like to illustrate a method that aims to support clients in repositioning themselves when they feel stuck within their meaningful relationships. Sometimes, clients are no longer able to see any new possibilities. They get trapped in certain patterns and cannot imagine how they will influence their own future. In such moments it can be useful to co-create imaginary contexts and the interactions that occur within them.

In this post, I would like to illustrate a method that aims to support clients in repositioning themselves when they feel stuck within their meaningful relationships. Sometimes, clients are no longer able to see any new possibilities. They get trapped in certain patterns and cannot imagine how they will influence their own future. In such moments it can be useful to co-create imaginary contexts and the interactions that occur within them.

I have learned in practice that when clients have the opportunity to imagine alternative scenarios, it often proves to be helpful in translating their experience into narratives of their own which relate how they wish to position themselves towards others, themselves, their past or their future. Our imagination truly moves us; it allows us to regain a sense of how we are affected and how we affect our environment. Through imagination, we can explore roles and relationships. We can consider the next step.

I will exemplify this method by sharing a small part of my journey with Rik and Suzy, parents of 60 and 55 years of age. They are experiencing a total impasse in life with their son Lucas. Rik and Suzy are seized by painful memories and ongoing conflict with their son who is extremely dismissive of them. Amidst all of this chaos, it has become very difficult for them to reflect on their own situation. They seem no longer able to grasp how they want to represent themselves or what they think they ought to do.

“Our situation is our situation and that is it.”

Rik and Suzy send me an email with a request for help. They have got two kids, a son Lucas, 16 years old and a son Felix, 24 years old. Suzy gave birth to 3 children, but Fran, their daughter, died from meningitis at a very young age. Rik and Suzy are really concerned about living with Lucas. They write in their email that Lucas does what he wants and does not look back. His outbursts are happening on a weekly basis but remain very unpredictable. Many things in the house have been destroyed, holes in the walls are reminders of past violence.

Recently, Lucas grabbed Rik by the throat, screaming and pinning him to the ground. Lucas’ school attendance is poor; he only does enough to keep out of trouble. The email also mentions huge difficulties with Felix in the past, but he suddenly went abroad two years ago and is now living in France. It looks like he is currently working on a farm, but that is uncertain. They don’t hear anything from him.

In their email, the parents write that they feel completely stuck but at the same time are reluctant to change anything about the situation. “Lucas seems to hate us. He has been diagnosed with ADHD when he was young and there were presumptions of autism, but he has always refused to talk to us, or any professionals.” Rik and Suzy write that they have waited for a long time to ask for help. They are really doubtful about whether therapy could be useful. “Our situation is our situation and that is it”.

When I invite the parents for a first meeting, it is a big effort to get the conversation going.  Suzy sits in front of me giving the impression of feeling uncomfortable and miserable, hesitant about every word. She primarily seems to want to come across as polite. Rik is even more taciturn; he stares at me with a fixed gaze, repeating slowly what they mentioned earlier in their email. It takes two hours before I understand a bit more about their history. There is a lot of silence that feels confusing.

Suzy sits in front of me giving the impression of feeling uncomfortable and miserable, hesitant about every word. She primarily seems to want to come across as polite. Rik is even more taciturn; he stares at me with a fixed gaze, repeating slowly what they mentioned earlier in their email. It takes two hours before I understand a bit more about their history. There is a lot of silence that feels confusing.

After the meeting, I go through my notes, circling what struck me the most. First: the very violent episodes that the family has experienced in living with Felix, the oldest son. I hear stories about a very rigid and verbally powerful young man. Stories about threat and coercion and of violence that make me think about torture. Felix would sometimes take out his belt and whip it around. All members of the family got hurt.

Second: the narrative of remorse and regret when Rik and Suzy talk about Lucas’ behaviour. Lucas either totally avoids his parents, or he confronts them with an unpredictable and threatening attitude. According to the parents, Lucas has suffered a lot under the tyranny of his brother and will never forgive them. Lucas wants to be left alone and is aiming to leave home as soon as possible. Rik mentions that earlier in the week, Lucas pushed him aside roughly when doing the dishes, calling him a ‘fucking wimp’. There is no constructive interaction between them. I schedule some more meetings with the parents.

Huge doubts.

In the next couple of meetings, I try to provide some space for the suffering there has been and the suffering that is ongoing. We talk about the violence then and now, about the loss and mourning that surrounds Fran, about their friends and their current contacts. Given the seriousness of the situation, we arrange for Suzy to inform the community police officer. He has visited the family twice but did not have a chance to talk to Lucas. One time Lucas refused, the other time he fled the house.

Having been listened to, the parents seem relieved and feel slightly less alone. We also talk about informing some friends and family as to how they could engage in supporting the parents. The untouchable reality of Lucas’s threats and violent eruptions becomes less self-evident. At the same time, the parents express huge doubts about whether to continue with our collaboration.

This in fact does not seem to have much to do with a fear of how Lucas could react. The question they ask themselves is: “what’s the point?” I start to understand that Rick and Suzy cannot engage with the idea of change if this idea is not related to their parenthood and their identity as a family. If they were to aim for change, this would have to be in the context of what they consider their duty and responsibility as parents.

But it is this experience that is so hard for them to grasp, as the history of their parenthood is told as a hopeless case, ending in the dominant behaviour of their son. In all of this one-way traffic, Rik and Suzy experience their life as something that is happening to them, rather than something they are able to construct themselves. In the next meeting, we consider different angles on change.

What does it mean to take care of their son in the current situation? Could changing that situation be a way of caring for him? What does it actually mean to take care of your child, when the child screams bloody murder and tells you to ‘f… off’? What does it mean to love your child when he doesn’t love you, or at least seems to have wanted to give that impression over the last two years? Could the narrative surrounding Felix – apart from being a story of rupture – also provide the soil for connection? Apart from their differences with Lucas, is there any commonality?

Through this exploration, more reflections on involvement, mattering and hurt appear. Could it be that, like his parents, Lucas might feel left behind, broken, after having been swept off his feet by ‘hurricane Felix’? Could it be that everybody is just trying  to survive? Could it be they are all trying to hold on to their lives, though in different ways? Is the parents’ submission to Lucas a way of surviving? Can we see Lucas’ violent actions as his way of surviving?

to survive? Could it be they are all trying to hold on to their lives, though in different ways? Is the parents’ submission to Lucas a way of surviving? Can we see Lucas’ violent actions as his way of surviving?

Maybe. Possibly. In some moments, I notice how Rik and Suzy are really reflecting and considering these ideas, their bodies upright, sitting on the front of their seats. But at other moments, they just seem to be ‘not there’, and our considerations get stranded on the shoreline.

The atomic shelter.

The image of the hurricane and its devastating effects stays with me. I think about it some more, and the image develops further in my mind. In the next meeting with Rik and Suzy, I tell them how our considerations have been keeping me busy. I ask them if I could invite them into an imaginary exercise. Rik tells me that this is fine with him.

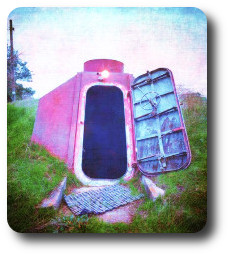

Evoking all sorts of sensory perceptions such as sound, colour, and scent, I ask Rik to imagine being inside of an atomic shelter. It is a bunker, a place deep underground where you hide, waiting for the war to end. You are there, together with a child. For a while, you are waiting in fear, because bombs are dropping and canons roar. Everybody tries to remain as silent as possible. After some time, it all quiets down. You decide to climb the small metal steps towards the heavy hatch. You open it up and take a first look around. You notice how the worst is over. Everybody should be able to go outside now.

I ask Rik to imagine looking down the staircase tunnel. He engages with the whole scene. How do you think your child notices that you want to go outside? How do you support your child in climbing the steps? What does he need from you in order to do that? Rik squeezes his eyes. Working through this allegory, I notice how Rik, for the very first time since we have met, is becoming very present. Within this given context, he is shifting from a position of being like an extra in a movie film to someone whose experience has become centralized. In his imagination, Rik is talking to his son like a father:

“I talk to him. I tell him: I get it, son. I get that you are afraid. It’s actually alright now. I have seen it myself. I wink at him. It’s alright son. Take your time.” In his imagination, Rik is moving, he is trying to survey his situation. He is differentiating his own experience from that of his son, assessing how his actions will affect them both. He is making choices.

“I talk to him. I tell him: I get it, son. I get that you are afraid. It’s actually alright now. I have seen it myself. I wink at him. It’s alright son. Take your time.” In his imagination, Rik is moving, he is trying to survey his situation. He is differentiating his own experience from that of his son, assessing how his actions will affect them both. He is making choices.

Then, he is silent for a minute. He looks at me. “ Do you think that my house is an atomic shelter?” I tell him that I wonder how I should perceive his house and that I’m also wondering how he perceives his house. “If I would think of your house as an atomic shelter, Rik…then are you in it, or out of it?” Rik throws me a little smile and we share another moment of silence. “That is a really tough question.” I nod.

Rik tells me that he had once read an article in the newspaper about a recently discovered atomic shelter from World War II, somewhere below the floor of a school. A local resident told the paper that he had actually stayed in there, with a gas mask on his face.

New considerations.

Shortly after this meeting, a major conflict occurs at home; Lucas kicks in a door and smashes all of the glass from the china cabinet. I receive an email from the parents, stating that they have to think about whether it is a good idea to continue the therapy because maybe it is impossible to really change anything. I write back to them, saying that I am and will remain ready to work with them, knowing it will be a strenuous road.

to work with them, knowing it will be a strenuous road.

One week later I receive an email from Rik. He sends me an article, titled “Bomb shelter from WWII discovered under playground: students with gas masks on used to wait until the bombing was over”. I mail back to him, saying that I suspect he is thinking a lot about himself and his son. And that I am thinking about them a lot as well.

This blog is based on a lecture, given at the conference surrounding the book ‘Geweldloos verzet: bespiegelingen vanuit theorie, onderzoek en praktijk’ (Nonviolent resistance: reflections on theory, research, and practice) on 8 February at the University of Brussels)

Willem Beckers

Senior Faculty Member Interactie Academie & Systemic Psychotherapist