Walking through the forest, I come upon a tiny pond, hardly three feet deep. A fence, incongruously slicing through the naturalness of the old growth wood encloses the small body of water that is part of it. Additionally, a sign warns of an imminent safety risk; it depicts a bright red bar across the silhouette of a diver, with a caption reading:

Walking through the forest, I come upon a tiny pond, hardly three feet deep. A fence, incongruously slicing through the naturalness of the old growth wood encloses the small body of water that is part of it. Additionally, a sign warns of an imminent safety risk; it depicts a bright red bar across the silhouette of a diver, with a caption reading:

“DANGER OF DROWNING”.

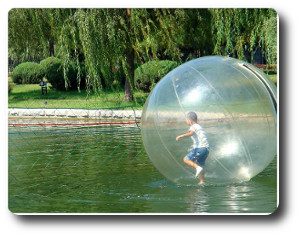

This has become a common site in our landscape. In an increasingly risk-averse culture, external interventions aim to protect us from almost any harm that might befall us. Yet, have we as a society examined possible longer-term harm that might be generated by some of our intense focus on safety and the ensuing attempts to regulate and control the material and social environments we move in? To be more concrete: How will the capacity of children to exert self-control develop differently, if adults rely increasingly on fences and exclusions to ensure safety from drowning – literally and metaphorically speaking? In which ways might such ever increasing external safety control diminish our children’s personal growth and their development of accomplishment in negotiating the dangers of complex environments?

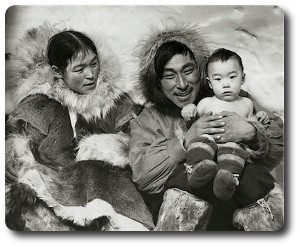

The anthropologist Jean Briggs joined an Inuit family in 1970 in order to study their culture. At this time, the Inuit she visited and studied were largely living a traditional life-style; this rendered very credible insights into the socialization that enabled her hosts to develop attitudes and behaviours which made it possible for them to negotiate and survive in one of the harshest and most dangerous natural environments on earth. The material environment necessitated social interaction that would enable survival of the group. One of the most striking observations she made early on was that the adults were highly self-controlled when it came to the regulation of their anger. Whilst there were many frustrations that could trigger angry feelings, Briggs was intrigued to find how able they were to keep their arousal down and remain calm, avoid escalation, and maintain a peaceful interpersonal atmosphere. She found them far more able to control their anger than she herself was. There will have been good reasons for the need to regulate anger so effectively: In the enclosed space of an igloo in Winter, when storms rage in the darkness outside and temperatures of around minus forty threaten one’s very existence, there can be no ‘time out’, no exclusion or isolation to protect others from an individual’s aggression – such responses would result in certain death. Sharp reprimand, punishment and escalating arguments would render life in the confined space of the Inuit family’s home emotionally unbearable and jeopardize their ability to cooperate – yet cooperation was essential for their physical survival. What the adults did to regulate their anger on a day-to-day basis soon became apparent to Briggs, yet she wanted to understand how they had become so extraordinarily accomplished in doing so? It is at this point that we can discover, how we can learn not only about them, but importantly learn from them…

During a temper tantrum, the Inuit parent would merely remain quiet and wait for the child to calm themselves; there was no  attempt to stop the child from showing aggression or restrain them, no regulation of the child’s arousal by the parent, nor would they exclude – no ‘time out’ for the Inuit child. There was no punishment. Shouting at children or reprimanding them violated Inuit parenting precepts, it was anathema to how they wished to raise the young. So then, what did the parents do? Briggs noticed that Inuit parents relied far more on initiating learning experiences that would enable their children to develop the innate capacity for self-control, instead of exerting external control when the children were overstepping the line of accepted behaviour. On one occasion, she observed a mother handing her little son a stone and playfully telling him to hit her with it. Once he had done so, she told him to do this harder and harder, eventually breaking out in cries of “ow, ow, that hurts”, enabling him to recognize the consequences of his action for the other and to empathize with them. Self-preservation was taught by telling tales, such as those of sea monsters that lurk in the depths of the ocean and pull children to their deaths; this helped them internalize an acute appreciation of risk and learn to avoid risk of their own accord. No fence lining the sea-front and cutting across the natural environment for the Inuit child.

attempt to stop the child from showing aggression or restrain them, no regulation of the child’s arousal by the parent, nor would they exclude – no ‘time out’ for the Inuit child. There was no punishment. Shouting at children or reprimanding them violated Inuit parenting precepts, it was anathema to how they wished to raise the young. So then, what did the parents do? Briggs noticed that Inuit parents relied far more on initiating learning experiences that would enable their children to develop the innate capacity for self-control, instead of exerting external control when the children were overstepping the line of accepted behaviour. On one occasion, she observed a mother handing her little son a stone and playfully telling him to hit her with it. Once he had done so, she told him to do this harder and harder, eventually breaking out in cries of “ow, ow, that hurts”, enabling him to recognize the consequences of his action for the other and to empathize with them. Self-preservation was taught by telling tales, such as those of sea monsters that lurk in the depths of the ocean and pull children to their deaths; this helped them internalize an acute appreciation of risk and learn to avoid risk of their own accord. No fence lining the sea-front and cutting across the natural environment for the Inuit child.

Years ago, a five-year-old boy demonstrating extremely aggressive behaviour was referred to me. He had hurt many other children and adults, and had recently seriously injured another child. One professional commented that he was “heading straight for Broadmoor”. What may be interpreted as a highly cynical comment also struck me as an expression of extreme helplessness by an adult who was part of a reactive endeavour to contain this child’s aggression, by attempting to pre-empt and avoid any risk he could pose to himself or others – yet could not hold the belief that growth was possible in this child. The adults were building ever higher ‘fences’ around the ‘ponds’ in his social environment. In our efforts to re-integrate him – let’s call the boy ‘Jimmy’ – into mainstream school (at the age of five, remember?!), we noticed the highly anxious tendency to control his environment to such a degree, that the risk of any harm whatsoever should be precluded. The narrative around the control of Jimmy’s environment aimed to be kind; thus the professionals’ views were rendered in the language of disability: “Jimmy can’t cope with assembly, so his teaching assistant stays back in the quiet room with him.” “Something about balls triggers Jimmy off, he absolutely needs to have the ball, so we can’t let him join in any football games.” “He flies into rage whenever he hears a ‘no’, so he can’t cope in the classroom where he would need to follow the rules that apply to the other children; that’s why we only have him in the classroom for about ½ hour every day, so that it’s not too much for him.” Proclamations of Jimmy’s inability to exert self-control were communicated as a description of immutable traits. Carole Dweck sees in such communication the expression of a ‘fixed mindset’, a mindset that is characterized by the strongly held belief that someone’s trait or traits are quasi fixed in stone, that growth is not possible in the here and now. Unsurprisingly, Dweck has been able to demonstrate that traits are less likely to change, there is less likely to be personal growth, if a person or the people around that person believe and communicate in their words, in the prosody of their speech and in their body language the belief that these traits are fixed and unchangeable characteristics of that person. In my view, fences around ponds also communicate such a belief.

Yet, invariably, the question arises whether we can conscience exposing the child to their social environment and thereby accept the inherent risk to them or to others around the child? Must we not keep someone like Jimmy out of the school assembly, out of the classroom and avert any risk he might pose to another child or to himself? Yet, what is rarely examined are the potential serious risks to longer-term safety that  are inherent in the pre-emptive, anxiety-driven measures which aim to control all aspects of the child’s environment. What can be seen as over-zealous attempts at controlling Jimmy’s environment are likely to cause him serious harm in the long run. The ‘fences’ of keeping Jimmy out of assembly, out of the classroom and away from ball games are milestones on the way to ever increasing social exclusion. The search for ‘root causes’ of Jimmy’s aggression in professionals’ conversations becomes a smoke screen that obscures this process of excluding him from ordinary contexts of normal life. Jimmy’s need to feel a strong sense of belonging is not met. Jimmy’s need to feel competent in negotiating the choppy waters of social interaction in the group he needs to feel he belongs to is not met. Jimmy’s need to feel emotionally safe and contained by adults who do not communicate permanent anxiety in the face of his aggressive potential, but instead a sense of self-assurance and confidence in his innate ability to grow as they care for him as a whole person is not met. As Jimmy runs up to more and more security fences in his life, as these central needs remain unmet, what trajectory does his development take? It is not, in my view, a far reach to assume that his aggressive potential will grow, that his innate ability to exert self-control and be mindful of the consequences of his actions for the well-being of others will diminish further as he has less and less exposure to the dangerous places of his social – and often material – environment. Jimmy will not have been made safe; he will suffer harm – to his emotional well-being, to his psychological functioning, to his mental health. When that happens, risk to others will increase with Jimmy’s increasing power and growing aggressive potential. Because of the harm he will cause others, the fences will have to get higher and higher. Others will get hurt, and eventually, Jimmy could face the ultimate barrier – the locked doors, the fences and the walls of Broadmoor Prison.

are inherent in the pre-emptive, anxiety-driven measures which aim to control all aspects of the child’s environment. What can be seen as over-zealous attempts at controlling Jimmy’s environment are likely to cause him serious harm in the long run. The ‘fences’ of keeping Jimmy out of assembly, out of the classroom and away from ball games are milestones on the way to ever increasing social exclusion. The search for ‘root causes’ of Jimmy’s aggression in professionals’ conversations becomes a smoke screen that obscures this process of excluding him from ordinary contexts of normal life. Jimmy’s need to feel a strong sense of belonging is not met. Jimmy’s need to feel competent in negotiating the choppy waters of social interaction in the group he needs to feel he belongs to is not met. Jimmy’s need to feel emotionally safe and contained by adults who do not communicate permanent anxiety in the face of his aggressive potential, but instead a sense of self-assurance and confidence in his innate ability to grow as they care for him as a whole person is not met. As Jimmy runs up to more and more security fences in his life, as these central needs remain unmet, what trajectory does his development take? It is not, in my view, a far reach to assume that his aggressive potential will grow, that his innate ability to exert self-control and be mindful of the consequences of his actions for the well-being of others will diminish further as he has less and less exposure to the dangerous places of his social – and often material – environment. Jimmy will not have been made safe; he will suffer harm – to his emotional well-being, to his psychological functioning, to his mental health. When that happens, risk to others will increase with Jimmy’s increasing power and growing aggressive potential. Because of the harm he will cause others, the fences will have to get higher and higher. Others will get hurt, and eventually, Jimmy could face the ultimate barrier – the locked doors, the fences and the walls of Broadmoor Prison.

Or maybe not: In Jimmy’s case, what we actually did was encourage his teachers to strike a careful balance between gradually increasing exposure and pre-emptive measures. First five minutes in assembly, then ten, then he stayed for the full length of the assembly. Of course, sometimes his teaching assistant had to whisk him out when she saw he was beginning to get agitated. Later, out of infant school, his teaching assistant in Junior school would run along the field, back and forth as Jimmy was dribbling the ball, ready to dash in if needed, mitigating risk but enabling him to join in, to belong, yet giving the message that belonging went hand in hand with self-control. When in anger Jimmy did start getting rough with another boy, his teaching assistant was close enough to intervene, and later, hours or days later, gave him the opportunity to make a reparation to the other child – and then re-join the football team. Still watchful, Jimmy’s teaching  assistant could gradually move further and further away, and one day, standing at a distance from the field and seeing his charge as a small figure running back and forth in pursuit of the ball, laughing and regulating his own excitement, he contemplated whether it may now be safe enough to risk not watching Jimmy at play at all.

assistant could gradually move further and further away, and one day, standing at a distance from the field and seeing his charge as a small figure running back and forth in pursuit of the ball, laughing and regulating his own excitement, he contemplated whether it may now be safe enough to risk not watching Jimmy at play at all.

Today, Jimmy attends mainstream secondary school. He plays in the football team and does not need an individual teaching assistant to be vigilant, to balance vigilance with inclusion any longer. Jimmy’s internal ‘self-control muscle’ has strengthened, even if he still faces challenges in the wake of many adverse life events he has had to suffer. Had the adults responsible for his care and education in the pursuit of safety continued to seek absolute control of his environment in order to pre-empt any risk at all, I believe strongly he would have continued to feel unsafe and would have grown to be more and more unsafe to others. The short-term gain of near complete risk avoidance will have given way to the long-term pain of even greater harm to the child and to others around him.

Sitting with my friend Dan Dulberger, with whom I share a strong commitment to the reduction of harm in human interaction and discussing what can amount to an un-reflected preponderance with and aversion to any risk at all, Jimmy came to my mind as many times before. In my mind’s eye, I see Jimmy sitting at the pond in the forest, no red bars and no fence. Perhaps his feet are dangling in the water, the mud oozing up between his toes, the reeds rushing in the breeze. He may not be very good at it yet, but by now, Jimmy has learned how to swim.

Dr Peter Jakob

Consultant Clinical Psychologist & Systemic Family Therapist

Director PartnershipProjects