I have had the pleasure of working with individuals with learning disabilities, both in adult and child settings, for 20 years. Across all roles, I have worked with parents, and an interest in all things parenting started to develop, an interest that peaked when I became a parent for the first time. I have also naturally found myself holding a position of resistance across roles: holding the needs of people with learning disabilities (and their families) in the minds of others at an individual level and at a service level and opening different perspectives in understanding psychological distress by taking a trauma-informed approach, especially understanding behaviour as a form of communication. I have always valued the role of the therapeutic relationship, taking a playful and measured pace in my work, but noticed an internal conflict with external drivers to ‘do’ and ‘improve’ an individual’s circumstances, for example, through ‘goal-based outcomes’ within the context of a therapeutic model.

I have had the pleasure of working with individuals with learning disabilities, both in adult and child settings, for 20 years. Across all roles, I have worked with parents, and an interest in all things parenting started to develop, an interest that peaked when I became a parent for the first time. I have also naturally found myself holding a position of resistance across roles: holding the needs of people with learning disabilities (and their families) in the minds of others at an individual level and at a service level and opening different perspectives in understanding psychological distress by taking a trauma-informed approach, especially understanding behaviour as a form of communication. I have always valued the role of the therapeutic relationship, taking a playful and measured pace in my work, but noticed an internal conflict with external drivers to ‘do’ and ‘improve’ an individual’s circumstances, for example, through ‘goal-based outcomes’ within the context of a therapeutic model.

Over the past 9 years, I have become immersed in children’s service, specialising in working with children with learning disabilities in a Children and Mental Health Service (CAMHS). Considering the child in the context of their relationships is central to all support offered to children and young people. Interventions that involve family members are essential for increasing awareness and insight into the experience and allow thinking about how factors within the family and the wider system may be contributing to, maintaining, or reinforcing the child’s difficulties.

Whilst offering a range of clinical interventions, NVR has provided a framework to support families to navigate to a position of strength and parental legitimacy in the face of trauma, adversity and violence. Dominant narratives within the wider system context for children with learning disabilities typically focus on the notion that the destructive behaviour of a child is a result of a disorder / problem within them, leading to dominance in the field of problem-saturated terminology, including: ‘challenging behaviour’. Within risk-orientated formal networks, the behavioural modification approach has dominated the field of learning disabilities. It is unsurprising then that parental beliefs are often that: ‘challenging behaviour is inevitable’, meaning that it can be so hard to feel legitimacy in naming violence. The impact of this is purported to contribute to a lack of resistance and commonly a position of accommodating violence and control from a child, with many parents reporting feeling powerless to effect change.

Whilst offering a range of clinical interventions, NVR has provided a framework to support families to navigate to a position of strength and parental legitimacy in the face of trauma, adversity and violence. Dominant narratives within the wider system context for children with learning disabilities typically focus on the notion that the destructive behaviour of a child is a result of a disorder / problem within them, leading to dominance in the field of problem-saturated terminology, including: ‘challenging behaviour’. Within risk-orientated formal networks, the behavioural modification approach has dominated the field of learning disabilities. It is unsurprising then that parental beliefs are often that: ‘challenging behaviour is inevitable’, meaning that it can be so hard to feel legitimacy in naming violence. The impact of this is purported to contribute to a lack of resistance and commonly a position of accommodating violence and control from a child, with many parents reporting feeling powerless to effect change.

A long-standing challenge within the field of learning disability services is shifting perspectives away from the medical model of disability where the impairment is considered the problem, and to the social model of disability, where structures within society are considered the problem. Thus, moving away from considering the problem as located within the child and seeking a label / diagnosis, to problems as existing (and are maintained) in the interactions between individuals, and taking a strength and need focus / identifying barriers and solutions within the child’s context.

I immediately saw that NVR offered families something different, and I was left wondering what was the difference that was making the difference (Gregory Bateman). I was aware of how the flow of life for parents with children with learning disabilities can feel like it is going upstream. I could see how harmful it felt to parents to feel like they were failing, and how harmful this was for the child. I witnessed the influence of the multiple layers of loss, including chronic sorrow and loss of the imagined child (Roos, 2002), and the threat that violence brings to the relationship. I was also interested in how parents could fall into ‘the dependency trap’ whereby an interaction pattern between child and parent maintains a situation in which the child’s functioning remains at sub-optimal levels and the parents’ at an overprotection level (Golan et al., 2016). Frequently, many parents would explain that NVR gave them ‘permission’ to do things differently, or enabled them to ‘follow their gut’ when dealing with behaviours that were challenging. This led me to think more about the role of parental legitimacy in NVR, wondering where parents get their sense of parental legitimacy from, and the traps that undermine a sense of parental legitimacy.

I immediately saw that NVR offered families something different, and I was left wondering what was the difference that was making the difference (Gregory Bateman). I was aware of how the flow of life for parents with children with learning disabilities can feel like it is going upstream. I could see how harmful it felt to parents to feel like they were failing, and how harmful this was for the child. I witnessed the influence of the multiple layers of loss, including chronic sorrow and loss of the imagined child (Roos, 2002), and the threat that violence brings to the relationship. I was also interested in how parents could fall into ‘the dependency trap’ whereby an interaction pattern between child and parent maintains a situation in which the child’s functioning remains at sub-optimal levels and the parents’ at an overprotection level (Golan et al., 2016). Frequently, many parents would explain that NVR gave them ‘permission’ to do things differently, or enabled them to ‘follow their gut’ when dealing with behaviours that were challenging. This led me to think more about the role of parental legitimacy in NVR, wondering where parents get their sense of parental legitimacy from, and the traps that undermine a sense of parental legitimacy.

I proposed 6 traps:

- Fear of being perceived as a bad parent

- The multiple layers of loss

- Societal / cultural narrative leading to a ‘disablist narrative’

- ‘The dependency trap’ (Lebowitz, Dolberger, Nortov and Omer, 2012)

- Dominance of the behavioural modification approach within the field

- Isolation / lack of resources

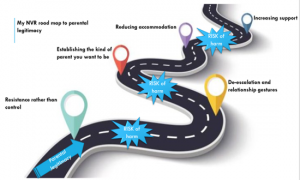

Key aspects of the NVR framework that appeared to address these traps and boost parents’ sense of parental legitimacy formed ‘my NVR road map to parental legitimacy’. This included: supporting parents to move through resistance rather than control; enhancing skills in de-escalation and relationship gestures; reconnecting / establishing the kind of parent you want to be, reducing accommodations and increasing support. This journey recognises the role of risk, and the dominance of risk in orientating services responses to parents, with an emphasis on supporting parents to resist dominant narratives when they undermine their sense of parental strength and legitimacy. I noticed how this journey provides the opportunity to influence the shame of experiencing violence as a parent rather than feel paralysed by it.

Key aspects of the NVR framework that appeared to address these traps and boost parents’ sense of parental legitimacy formed ‘my NVR road map to parental legitimacy’. This included: supporting parents to move through resistance rather than control; enhancing skills in de-escalation and relationship gestures; reconnecting / establishing the kind of parent you want to be, reducing accommodations and increasing support. This journey recognises the role of risk, and the dominance of risk in orientating services responses to parents, with an emphasis on supporting parents to resist dominant narratives when they undermine their sense of parental strength and legitimacy. I noticed how this journey provides the opportunity to influence the shame of experiencing violence as a parent rather than feel paralysed by it.

The different possibilities and positions available to parents have included a sense of hope, confidence, and strength, less searching for diagnoses / labels, more acceptance of their family life and increased independent functioning of the child. The layers of influence more widely include supporting services to shift the focus away from ‘problem saturated’ thinking; reducing stigma around seeking help with parenting challenges, and, promoting safe, stable and nurturing relationships as the goal for intervention.

I have noticed the parallel processes of how NVR has influenced both parents and my own positions: legitimising parents’ position of strength and giving them ‘permission’ to respond in certain ways and legitimised my leaning towards connection / therapeutic relationship – prioritising the ‘being’ rather than ‘doing’. Also, the anchoring functioning of focusing on the relationship has enabled the opening up of different perspectives on the ‘problem’, moving away from the story of ‘challenging behaviour’ that is limiting.

Dr Hannah Moore, Clinical Psychologist,

Accreditation Module participant, 2022